How to win in recruitingMike Nowoswiat and James Moss

|

As Jeremy Darlow explains in his book Brands Win Championships, “teens pick brands, pros pick contracts.” College athletics provide a unique, albeit contentious, dynamic in which players base their college decisions on a radically different criteria than professional players, who often opt to play for whichever franchise will pay the most. Stadium size, uniforms (read our article Fashion Wars on the influences of uniforms and apparel companies in recruiting), program prestige, coach prestige, coach persona, location, media exposure, fan sentiment, playing style, and academics are only a handful of the endless factors that play a role in an athlete’s decision. The net sum of all these influences becomes the program’s brand, which is then evaluated by millions of high school athletes. Each athlete is sure to perceive each school uniquely, but the masses will come to a general sentiment on which school is better than the next. It is absolutely critical for a college football program’s brand to be perceived ahead of its competition by the majority of high school athletes--or at the very least, the majority of high school athletes in a desired segment of the high school athlete population. Jeremy Darlow spoke to us about this dynamic, and shared: "Few brands reach omnipresent levels in which they can be all things to all people, which plays into a team’s favor. If you can identify the brand space that is genuinely unique to your program, you are instantly #1 in the country for that idea."

Branding

We wanted to find out exactly how high school football players perceive the Power 5 schools, so we asked 224 recruits to grade their interest and desire in each program as if they were the number one recruit in the country (i.e. they had offers from every school). This process gave us a peek into the minds of the most important demographic: teenage football players. Everyone who follows college football surely has an opinion on every program and, consciously or unconsciously, has their own personal ranking system comprised of all the brands. However, a middle-aged man probably has a different, more favorable perception of a once-gloried program than a young teenager who never witnessed a winning season. Rather, the lifeblood of a college program lies in the minds of high school football players. These rankings show us the critical hierarchy of schools within recruits’ minds. This is the closest thing to the NCAA’s version of the NFL draft. The teams at the top of these rankings will get the first picks and the teams at the bottom of the rankings will get the leftovers. Pro teams can squander high draft positions through poor talent evaluation and thus poor draft selections while college teams can squander favorable brand positioning with poor talent evaluation, poor recruiting execution, or poor player development. However, in terms of raw “draft capital,” this is how teams position themselves for future success. Pro teams tank seasons and acquire additional draft picks to improve positioning. College teams hire creative marketing staffers and build fancy new facilities to improve positioning.

Why is this critical? Whereas sports like basketball or even professional football can be so greatly influenced by one individual or a small number of individuals (i.e. outliers), college football is an exercise in the principles of statistics. One of the first lessons in Statistics 101 is about the probabilities associated with flipping a coin. Of course, the true probability of landing heads on any given coin flip is 50%. However, if you flip a coin ten times, there is a decent chance you will get an 8:2 heads:tails outcome due to the low number of overall coin flips. If you flip a coin 1 million times, it is impossible to get a 8:2 heads:tails ratio due to the high number of coin flips. Instead, you will get a near perfect 5:5 heads:tails ratio. With each additional coin flip, the ratio of heads to tails will move closer to the true probability of 0.5. To connect this analogy back to football, think about these brand rankings as a ranking system of the true probabilities assigned to each program’s likelihood to land any given high school recruit regardless of circumstance. Clemson would then have the best probability to land any recruit it wants, whether it be the number one recruit in the country or the number 5,000 recruit in the country. Stanford would have the best probability to land an academic-minded recruit over the likes of Duke, Georgia Tech, Vanderbilt, and Northwestern. Kansas would have the worst probability to land any given recruit when competing against its fellow Power 5 brethren.

Darlow added, "The more you invest in quality marketing, the more sales tend to improve. Once programs realize that they themselves are brands, and that the recruits they are selling their school to are the buyers of those brands, they will recognize the necessity to invest in marketing. Imagine a world where the top prospects are beating down your door, not the other way around."

Why is this critical? Whereas sports like basketball or even professional football can be so greatly influenced by one individual or a small number of individuals (i.e. outliers), college football is an exercise in the principles of statistics. One of the first lessons in Statistics 101 is about the probabilities associated with flipping a coin. Of course, the true probability of landing heads on any given coin flip is 50%. However, if you flip a coin ten times, there is a decent chance you will get an 8:2 heads:tails outcome due to the low number of overall coin flips. If you flip a coin 1 million times, it is impossible to get a 8:2 heads:tails ratio due to the high number of coin flips. Instead, you will get a near perfect 5:5 heads:tails ratio. With each additional coin flip, the ratio of heads to tails will move closer to the true probability of 0.5. To connect this analogy back to football, think about these brand rankings as a ranking system of the true probabilities assigned to each program’s likelihood to land any given high school recruit regardless of circumstance. Clemson would then have the best probability to land any recruit it wants, whether it be the number one recruit in the country or the number 5,000 recruit in the country. Stanford would have the best probability to land an academic-minded recruit over the likes of Duke, Georgia Tech, Vanderbilt, and Northwestern. Kansas would have the worst probability to land any given recruit when competing against its fellow Power 5 brethren.

Darlow added, "The more you invest in quality marketing, the more sales tend to improve. Once programs realize that they themselves are brands, and that the recruits they are selling their school to are the buyers of those brands, they will recognize the necessity to invest in marketing. Imagine a world where the top prospects are beating down your door, not the other way around."

Recruiting Results

How do these brand rankings get translated to signing day results? Since the beginning of the recruiting service era (1999-2000), every national champion has had at least one recruiting class on its roster with multiple five star recruits. On average, there are only 7.7 teams—never less than five or more than nine—each year with multiple five star players. Only Clemson, Ohio State, Penn State, Georgia, USC, Alabama, and Texas landed multiple five stars in this year’s 2018 class. The first five schools all reside in the top 5 of the brand rankings while Alabama and Texas still have two of the most notable brands in the country. Why is this significant? Because most of our respondents have never been recruited by these top-tier colleges. Yet, despite all the phone calls, letters, text messages, unofficial visits, or any other obscure recruiting tactics that coaches deploy to attract elite talent, the final recruiting rankings align precisely with the high school demographic’s perceived brand rankings. The actual act of recruiting, apparently, is one giant charade. Is it necessary? Sure. Will marginally better recruiting execution lead to better results? No.

This distribution leads us to identify different tiers of brands within the rankings. Each year, the top 7.7 teams are therefore the teams that recruit at the highest level and give their team a statistical chance to win the national championship over the next four years while that recruiting class is in college. We will call this ‘Tier One’, which is comprised of the brands that are capable of winning recruiting battles against any other brand in the country since five star recruits, more often than not, have offers from virtually every school.

This distribution leads us to identify different tiers of brands within the rankings. Each year, the top 7.7 teams are therefore the teams that recruit at the highest level and give their team a statistical chance to win the national championship over the next four years while that recruiting class is in college. We will call this ‘Tier One’, which is comprised of the brands that are capable of winning recruiting battles against any other brand in the country since five star recruits, more often than not, have offers from virtually every school.

Excludes Tier 1 Recruiting Classes

Excludes Tier 1 Recruiting Classes

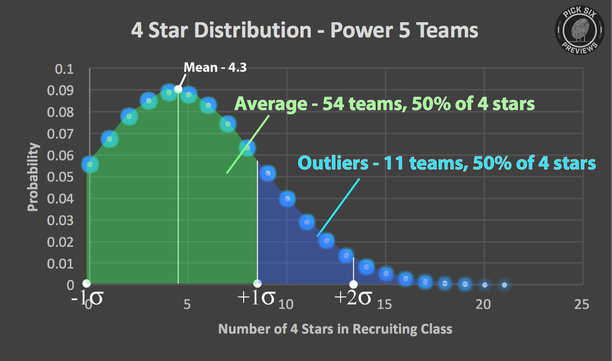

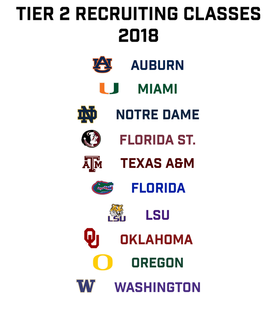

Teams in the next tier, ‘Tier Two’, struggle to consistently win their share of head-to-head battles against Tier One teams, but maintain a similar advantage over the lower tiers. Since there are plenty of four stars for both Tier One and Tier Two brands to share, these teams usually round up great recruiting classes chock full of four star players. Tier Two brands are comprised of teams that attract more than one standard deviation from the average number of total four stars in each Power 5 team's recruiting class. The average Power 5 team recruits 4.3 four star recruits in each recruiting class since 2003. The standard deviation of this distribution is +/- 4.47 four star recruits. Thus, 84.1% of teams recruit within one standard deviation of the average 4.3 four stars per recruiting class, which comes out to somewhere between 0 and 8.8 four stars in each of those recruiting classes. However, 15.9% of teams, which comes out to about 11 teams each year, recruit beyond this standard deviation with greater than an average of 9 four stars in their recruiting class. This small contingent of teams is able to reel in about half of all the four star recruits each year. In addition, the majority (56% to be exact) of all final AP top 15 teams have at least one recruiting class on their roster that made it into this Tier 2 outlier category. Auburn, Miami, Notre Dame, Florida State, Texas A&M, Florida, LSU, Oklahoma, Oregon, and Washington make up the Tier Two this year as all schools recruited at least 11 four star recruits (the average number of four stars per team was higher than average this year). All ten teams lie within the top 24 of our brand rankings. Taking the Tier One teams into consideration, 17 of the top 24 brands made it into either Tier One or Tier Two. No team ranked 25th or lower achieved Tier One or Tier Two status. After these top two tiers, we begin to see diminishing returns for the higher ranked teams still within the “average” band of +/- one standard deviation.

what about the money?

Note: Revenue figures not available for private institutions

Note: Revenue figures not available for private institutions

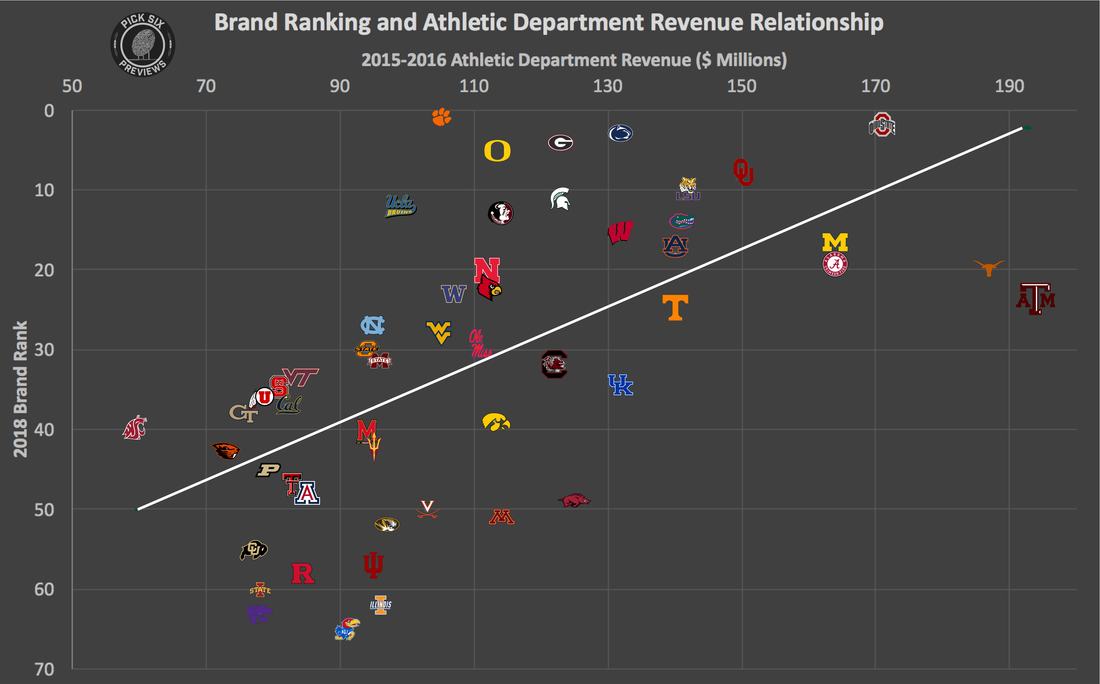

When discussing how revenue affects branding in 2018, we decided to look back a few years (2015-2016) for revenue figures assuming there is a lag between income and results. If we look back at revenue generated in 2015-2016 and compare it to our “Tier One” schools, it isn’t who jumps off the page--it's who isn’t on the page at all. The number one ranked team in our brand rankings, Clemson ($104.8 Million), generated the 27th most revenue in 2015-2016. This isn't to say that money isn't important, of course, as there is a clear linear relationship between revenue generated and brand power. However, it's evident that recruiting results are tied closer to brand ranking than revenue.

So what is the the common denominator among teams like Oregon, Miami (revenue not reported), and Clemson? All three teams cracked the top seven brands, yet didn't come near the top seven in revenue. They are all well-defined brands with deliberate brand strategies. They don't have the history or mystique of an Alabama or a Penn State but they have in fact created their own aura from scratch. Oregon has never won a National Title, but was the first to brand speed and tempo, and also has the ability to wear a different uniform combination for every game from now until the year 3344. They are one of the hottest brands in college football and this is reflected in their brand ranking (#5) despite coach turnover. Miami is still riding its wave from the 80s with “The U” despite under performing for the better part of the most recent decades. The U is still considered one of the “coolest” brands in college football. In a recent rebranding period, Miami brought back several of their uniform combinations from the 1980’s, and meshed that with their new-age turnover chain. Finally, Clemson has Death Valley, Howard's Rock, the charismatic Dabo Swinney, and a recent National Championship to sell. These three programs have found a way to differentiate themselves in the eyes of teenage student athletes with their brand from the blue bloods and other non-traditional powers in the sport of college football.

How about the schools with financial resources and solid brand recognition, yet relatively poor recruiting results? Wisconsin can barely land a single 4 star recruit yet appears in the top 16 of both our brand rankings and revenue rankings. Darlow described an issue he frequently sees, stating: "Too many schools are leading with the same three or four recruiting pitches; things like playing time, head coach prowess, facilities...and every program is a “family” these days. As is the case in any industry, when you go blow for blow with your competition, you’ll eventually lose to the bigger, stronger opponent." Oregon and Clemson don't try to be Alabama and Ohio State. You could make the case that Wisconsin does.

So what is the the common denominator among teams like Oregon, Miami (revenue not reported), and Clemson? All three teams cracked the top seven brands, yet didn't come near the top seven in revenue. They are all well-defined brands with deliberate brand strategies. They don't have the history or mystique of an Alabama or a Penn State but they have in fact created their own aura from scratch. Oregon has never won a National Title, but was the first to brand speed and tempo, and also has the ability to wear a different uniform combination for every game from now until the year 3344. They are one of the hottest brands in college football and this is reflected in their brand ranking (#5) despite coach turnover. Miami is still riding its wave from the 80s with “The U” despite under performing for the better part of the most recent decades. The U is still considered one of the “coolest” brands in college football. In a recent rebranding period, Miami brought back several of their uniform combinations from the 1980’s, and meshed that with their new-age turnover chain. Finally, Clemson has Death Valley, Howard's Rock, the charismatic Dabo Swinney, and a recent National Championship to sell. These three programs have found a way to differentiate themselves in the eyes of teenage student athletes with their brand from the blue bloods and other non-traditional powers in the sport of college football.

How about the schools with financial resources and solid brand recognition, yet relatively poor recruiting results? Wisconsin can barely land a single 4 star recruit yet appears in the top 16 of both our brand rankings and revenue rankings. Darlow described an issue he frequently sees, stating: "Too many schools are leading with the same three or four recruiting pitches; things like playing time, head coach prowess, facilities...and every program is a “family” these days. As is the case in any industry, when you go blow for blow with your competition, you’ll eventually lose to the bigger, stronger opponent." Oregon and Clemson don't try to be Alabama and Ohio State. You could make the case that Wisconsin does.

Tying it all together

As we mentioned in our article Fashion Wars, the idea of a recruit choosing such a life-altering decision on what amounts to a "gut feel" may not sit well with some. But as each large state school constantly benchmarks against other large state schools, and each technology school constantly benchmarks against other technology schools, the differences between Power 5 colleges can be razor thin. Of course a recruit will want to choose a school where he can receive a top education. The US News and Princeton Review top 100 college rankings are littered with Power 5 teams. Likewise, a recruit will want to choose a school that will give him the best shot at playing in the NFL. Two years ago we analyzed whether or not top schools like Alabama are actually better at preparing players for the NFL, and the results proved that the likelihood of getting drafted does not get better by playing for a better team. The reality is that recruits have great choices at just about any Power 5 school when it comes to the "important" criteria, such as academics or NFL preparation. When all else is relatively equal, recruits will then default to the program with the most momentum and buzz, the school that will impress his community members the most, the destination university that is sure to provide him 3-4 amazing years, or the childhood favorite.

Brand perception is not only one of the most important assets to an athletic department, but it is one of the easiest assets to change as well. Darlow describes in his book that perception, recruiting, winning, and money make up the four phases of an Athletic Program Life Cycle, in that order. All four phases are interrelated, yet the ability to affect the different phases is not equal. It is difficult for an athletic director to wake up and say, "I want to make 20% more money this year." It is more realistic for an athletic director to say, "I want to improve my brand perception." Perception in turn affects recruiting, which affects winning, which affects revenue. Each phase is most greatly influenced by the preceding phase. This explains why the recruiting results have a stronger correlation with our brand rankings than the revenue rankings. We documented how Clemson, a relative newcomer, topped the brand rankings yet was only 27th in the trailing revenue rankings. As the life cycle evolves, we expect Clemson's improved perception, recruiting, and winning to drive it's ranking up the revenue charts in years to come. In short, the name of the game in college athletics is perception. Perception is the product. Get perception right, and the rest will take care of itself.

Brand perception is not only one of the most important assets to an athletic department, but it is one of the easiest assets to change as well. Darlow describes in his book that perception, recruiting, winning, and money make up the four phases of an Athletic Program Life Cycle, in that order. All four phases are interrelated, yet the ability to affect the different phases is not equal. It is difficult for an athletic director to wake up and say, "I want to make 20% more money this year." It is more realistic for an athletic director to say, "I want to improve my brand perception." Perception in turn affects recruiting, which affects winning, which affects revenue. Each phase is most greatly influenced by the preceding phase. This explains why the recruiting results have a stronger correlation with our brand rankings than the revenue rankings. We documented how Clemson, a relative newcomer, topped the brand rankings yet was only 27th in the trailing revenue rankings. As the life cycle evolves, we expect Clemson's improved perception, recruiting, and winning to drive it's ranking up the revenue charts in years to come. In short, the name of the game in college athletics is perception. Perception is the product. Get perception right, and the rest will take care of itself.

For further discussion about branding in college football, email us at mike@picksixpreviews.com!