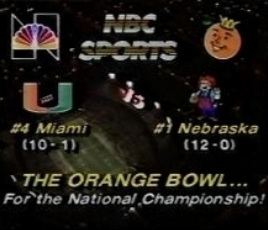

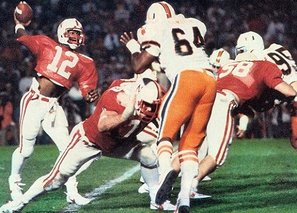

The 1983 Nebraska Cornhuskers were so highly-touted and feared that when NFL star John Riggins was asked of his upcoming schedule, he replied, “Hey, at least we don’t have to play Nebraska.” Tom Osborne’s “Scoring Explosion” was firing on all cylinders and the national media was regarding this team as the greatest in college football history. Awaiting Goliath in the Orange Bowl was hometown David, the upstart Miami Hurricanes led by Howard Schnellenberger. The vaunted Huskers needed a fumble-rooskie trick play and a late comeback to draw within a point with just 48 seconds left. Trailing 31-30, Osborne made the honorable decision to go for the two-point conversion and the outright victory, even knowing that a tie in all likelihood would have still resulted in Nebraska’s 3rd national championship. As Turner Gill’s pass fluttered hopelessly to the turf – the college football landscape shifted forever, and the two programs became linked eternally.

For the first time since Miami became “The U” as we know it, the Canes will travel to Nebraska to renew the rivalry Saturday night. These two programs are almost complete opposites in virtually every way, but now as fallen dynasties they have that one overarching link in common: the drive to return to national prominence.

NEBRASKA’s RISE TO 1983

In the 5 years before Bob Devaney took over the reigns at Nebraska, the program went 15-39 and all 5 were losing campaigns. His 9-2 mark in his opening season (1962) put the Nebraska program on the map, as did the win over Michigan in the Big House. His decade-long stint ended with back-to-back National Championships, with the 1971 team still discussed today as an all-time great. He handed over the keys to the Big Red Machine to then-offensive coordinator Tom Osborne. Osborne built the program on a power rushing attack, with heavy doses of option and trap plays. His offense was based on strategy, discipline, and strength; in addition to his outstanding football acumen, Osborne installed revolutionary programs to better the program. The strength and conditioning program was the best in the land, and Nebraska created the “Unity Council” furthering the team’s character, accountability and commitment. The state of Nebraska lacked the population density for 11-man football in most of the state, and by sheer geography, many of the nation’s top recruits were located far away. But Osborne perfected the walk-on program. State-wide, it was a goal to someday don the scarlet and cream, and players would take a shot at walking on to NU. This only invigorated the state more, as small towns would rally around their former local stars as they pursued a shot at big-time football. Nebraska won 9 games or more in all 25 seasons with Osborne at the helm. At first, his obstacle to the national title was Big-8 rival Oklahoma, who spoiled many seasons and title runs. After finally getting past the Sooners, Nebraska was given the unfortunate task of playing Miami – in their home stadium, the Orange Bowl. First it was 1983, then twice more Nebraska faced the same fate with seasons ending with sour oranges against the hometown “U.”

MIAMI’s RISE TO 1983

University of Miami was always known for just its elite academics and proximity to the beaches, but visionary coach Howard Schnellenberger was determined to change that. He branded the Hurricanes around the infamous “U” logo, and made it a mission to lock down what he called “the State of Miami.” South Florida was absolutely loaded with some of the best high school football talent in America; Schnellenberger had All-America teams in his own backyard. It took a few years to start gaining excitement around the program, but on that fateful night in the 1984 Orange Bowl, Miami had arrived. It was Schnellenberger’s 5th team, and first full recruiting class, that burst onto the scene. Behind a strong passing attack led by Bernie Kosar, and Florida’s finest skill players on both sides of the ball, the Hurricanes took the nation by storm. Just as Osborne was attempting to win his first crown, the hometown Canes stole it from his grasp and would win 3 more before he finally held the crystal football. SINCE “THE GAME” – THE DYNASTIES Miami won 4 national championships in 9 years – two of which they defeated Nebraska in. “The U” earned the title of “Team of the 80’s,” and did so with flash. They brought a new approach to the sport, one centered on brash, in-your-face behavior before, during, and after the game. Their revolutionary antics earned them somewhat of a bad-boy reputation to go along with their aerial assault and world-class speed. On the other side of the coin was Nebraska with their rushing attack, strength, and class that reflected their noble coach. While Miami paraded to their string of titles, Nebraska was trudging along with consistent 9 and 10 win seasons but failing to claim the elusive glory of the national championship. While his home state was producing strong players, Osborne went down to the Speed State to find his option quarterback gem, Tommie Frazier of Bradenton, FL. Coming up a missed field goal short of the 1993 National Title, Nebraska was back again for yet another bout with Miami for the title. While Brook Berringer played efficiently for most of the game, it was Frazier who delivered in the 4th quarter: his QB trap set up the game-winning score as Nebraska outlasted Warren Sapp and the hometown Canes. Nebraska would go on to win the national title in 3 of 4 seasons (1994, 1995, 1997) while Miami overcame some 1990s sanctions to claim the 2001 title (against Nebraska again). Atop of the college football landscape for so long, no one could have predicted just how far these perennial powers would fall off. THE DOWNFALL

From the year of Miami’s 1st national title to its final appearance in one (1983-2002), the teams are #1 and #2 in wins, nationally. But in the 11 seasons since, the former powerhouses check in at 16th (NU) and 30th (Miami). Neither team has won a National Championship or Heisman since 2001, and neither has won a conference title in over a decade. Nebraska’s downfall can ultimately be pinpointed to that same 2001 National Championship, a 37-14 beatdown loss to Miami. The Canes destroyed them in every phase of the game, but symbolically ended the era of the triple option. With its identity gone, Nebraska went for an outside hire it would regret forever: pass-happy Bill Callahan. Not only did he shake up the whole culture of the program, Callahan cut off ties with loyal alumni. This failed experiment was bookended by 5-7 seasons, ending with his firing in 2007. While Bo Pelini has brought Nebraska back to some level of respectability, their failure to win the big games or conference titles, and frequent blowout losses or meltdowns have kept Big Red from resembling the dynasty of old. No team in America has to work harder at recruiting, given the location. Even worse, it is becoming harder to have success with the “tradition of excellence” pitch, as current high school seniors were just one year old in the year of NU’s last national title (1997). Miami was riding a 34-game win streak into the 2002 Fiesta Bowl, heavily favored over Ohio State. In what will go down as one of the best games ever, the Buckeyes prevailed in double overtime and sent the first blow to the new millennium Hurricane dynasty. Many claim that coach Larry Coker only rode the success of Butch Davis' recruited players, and the win/loss stats can attest to that. The wheels started to fall off in his 4th season, and Coker lost total control in 2006, rallying to finish 7-6, the school’s worst record in over a decade. The Randy Shannon years saw no notable success, and Al Golden took over an investigation-ridden program trying to step out of the dark shadow of the Nevin Shapiro fiasco. Over the last decade, Miami has lost control of the Speed State, as rivals Florida State and Florida have both won national titles and continue to out perform the Canes on the recruiting trail. THE RETURN Saturday, let’s throw the Big Ten’s woes and Miami’s early-season loss out the window and focus on the revival of this historic matchup of iconic football brands. While the game doesn’t have a crystal football on the line, it carries importance to both fan bases and the sport itself, as both climb back to national prominence. These are the national spotlight games that both so desperately need to start winning consistently. The two opposite programs are linked together Saturday night, and for as long as it takes until they are both competing for titles again. And for the sake of the sport itself, we hope it’s sooner rather than later. |

2014 PREVIEW

|

|

|

© 2025 Pick Six Previews LLC. All Rights Reserved. For Informational Purposes Only

Privacy Policy |